Key Moments in Western Culture

The

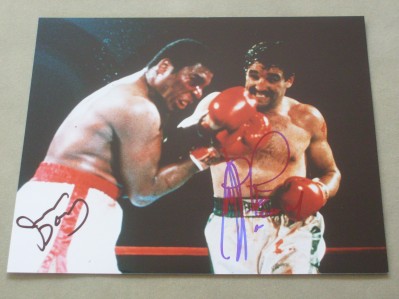

Holmes-Cooney Fight

By RAR

Gerry Cooney,

like the rest of us, was living in a special space in 1982. The world

was right on the cusp of another of those seven-year cycles, in which

our experience of life goes through fundamental change, fragmenting

families and communities and further rending our sense of shared

experience. Fashions, styles, sounds, manners, behaviors, technologies,

entertainments – everything that was familiar to us in the 1970s was

changed by the time we reached the early 80s.

Our sense of modernity had

been transmogrified by the advent of cable television, and by new media

offerings like the Cable News Network (CNN), Music Television (Mtv), and

an ever-growing list of television alternatives. This would ultimately

destroy the monopoly that the legacy networks CBS, NBC and ABC had

long-enjoyed over the American television audience, and it would

marginalize what had been unifying forces for generations of viewers by

virtue of having provided all there had been to watch on television. We

had all watched major historical events together, like the events of

1963 surrounding the Kennedy assassination, followed shortly thereafter

in 1964 with The Beatles appearances on the Ed Sullivan Show, and we had

shared important cultural touchstones like “All In the Family”,

“Laugh-In”, and “Saturday Night Live”. Television had always had its

detractors, but with the proliferation of Cable TV channels, the notion

of the “boob tube” was consigned to the past, overwhelmed by a wave of

niche programming that sometimes seemed pretty smart, and in that

process a new era of media absorption was born. Television sets started

to proliferate in peoples’ homes, installed in bedrooms, kitchens, and

bathrooms. Kids, watching in the isolation of their bedrooms, would

start referencing programs that their parents had never heard of, and

would never watch. “Beavis and Butt-Head” comes to mind, and so new

models of behavior emerged.

After the dourness of the

late-70s, when the Carter Administration had encouraged Americans to

live austere lives, President Ronald Reagan represented a sense of

renewed energy in America, even if by 1982 Reagan’s Budget Director

David Stockman was beginning to call his boss a “sunshine boy” for

enacting tax cuts that would soon thereafter need to be reversed to

recover economic stability. Reagan had an overly-rosy view of America’s

economic health and promise, but he was becoming embroiled in covert

actions and an arms scandal that were of a piece with the period. There

was a sense in the early 80s that everyone had a scam going; that people

were finding ways to profit around constraints, and that winners were

making money and leaving others behind. In fact, people started to think

of low income people as something less than just mere unfortunates,

uncharitably preferring to think of them as “losers”. Cocaine had become

the sine qua non of recreational drugs, and people were enjoying that

edge. There was an embrace of money and excess, and going against that

grain felt unfashionable. Punk music, analogous in its

anti-establishment sentiment to the Folk of the 60s and early 70s, had

come and gone, but its echoes seemed to spur a counter-insurgency

expressed through synthesizers and Disco beats. Music coming out of the

United Kingdom began to dominate the airwaves, in a time when few knew

that radio was in its dying throes, soon to be replaced by Satellite

transmissions such as Sirius XM (1990). New Wave music was unabashedly

Gay, in many respects, and it contributed to a shift in public

perception and a new openness toward alternative lifestyles and

homosexuality.

The one area that seemed to

show a retrograde motion was Black-White relations, and this was

reflected in Reagan Administration policies. Reagan, for some reason,

chose to begin his 1980 presidential campaign in Philadelphia,

Mississippi, near a site where three civil rights workers had been

murdered in 1964. He appointed conservative judges Antonin Scalia and

Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court, and from that platform he carried

out an assault on civil rights policies, including affirmative action

programs and voting rights. He slashed funding for the Comprehensive

Employment and Training Act (CETA), that provided needed assistance to

Black people. He sought a tax exemption for Bob Jones University, a

racist college, and backed Senator Jesse Helms in his assertion that

Martin Luther King was a disloyal American. Reagan popularized, among

some Republicans, the idea of black women as “welfare queens”, and he

championed the idea that Black leaders were “doing very well leading

organizations based on keeping alive the feeling that they're victims of

prejudice."

* * * *

Twenty-six-year-old

Gerry Cooney was the World Boxing Council’s #1-ranked Heavyweight in

1982. A six-foot-five boxer, with a great left hook, he was well-known

in amateur boxing circles, having worked his way up from a gangly

middleweight to become a heavyweight contender. Encouraged by his father

to get into boxing, the Long Island native won two New York Golden

Gloves Championships, including the 1973 160-lb Sub-Novice Championship

and the 1976 Heavyweight Open Championship. He had won international

tournaments in England, Wales, and Scotland, and by the end of his

amateur career had compiled a record of 55 wins and 3 losses. Twenty-six-year-old

Gerry Cooney was the World Boxing Council’s #1-ranked Heavyweight in

1982. A six-foot-five boxer, with a great left hook, he was well-known

in amateur boxing circles, having worked his way up from a gangly

middleweight to become a heavyweight contender. Encouraged by his father

to get into boxing, the Long Island native won two New York Golden

Gloves Championships, including the 1973 160-lb Sub-Novice Championship

and the 1976 Heavyweight Open Championship. He had won international

tournaments in England, Wales, and Scotland, and by the end of his

amateur career had compiled a record of 55 wins and 3 losses.

When Cooney decided to turn

professional, he fell under the tutorship of veteran trainer Victor

Valle, who had six decades of experience with top-ranked fighters. He

had guided the careers of champions

Alfredo Escalera (junior lightweight),

Esteban DeJesus (lightweight), and Billy Costello (superlightweight).

Valle saw the 225-pound Cooney as a guy who could win the heavyweight

championship if he was brought along carefully, and that he did,

carefully selecting Cooney’s opponents and developing almost a

father-son relationship with his fighter. Valle used to sing “Danny Boy”

to his Irish-Catholic liege in the dressing room before fights, changing

the words to “Gerry Boy”.

“Gentleman” Gerry Cooney won

his first twenty-five professional fights, recording 19 knockouts or

technical knockouts, and along the way his managers Mike Jones and

Dennis Rappaport turned him into a media figure in the New York City

market. Cooney was doing national television commercials by 1980,

becoming known as a sort of “great white dope” because the amiable giant

had a kind of a marketable Joe Palooka quality that worked. He seemed

sweet and sensitive. Though media exposure puffed up Cooney’s celebrity

profile, in boxing circles Cooney was not viewed as a threat to any of

the top heavyweights of the time, all of whom were Black in a period

where Blacks dominated the heavyweight division.

Cooney had largely established

his winning record on easy victories over nobody fighters, though he had

also defeated some legitimate pros in Charlie Polite, former US

heavyweight champion Eddie Lopez, Tom Prater, and John Dino-Denis. What

Cooney needed to establish legitimacy as a contender were victories over

big name Black heavies, and his first stop along that journey came

against Leroy Boone. The 216-pound Boone came into the fight with 12

wins and 3 losses. He was a good fighter, though just a training step

along the way toward getting Cooney paydays with bigger names and better

competition. That said, Boone was a guy who had never been knocked off

his feet, so he would offer a challenge that Cooney, the wannabe

champion, needed to face.

Cooney was unusually tall for

a fighter of his time, preceding an era in which heavyweights would

become even bigger. Only the six-foot-nine-inch Primo Carnera came to

mind to boxing commentators who struggled to describe Cooney’s physical

profile, which was tall but lacking in muscular definition. Cooney had

that kind of body that just does not get buff. He didn’t look like a

boxer, in many ways, or even like a guy who hit the gym regularly. He

seemed to have more hair on his chest than he had biceps or triceps,

and perched atop long, skinny, white legs, Cooney seemed cartoonish,

like a caricature of an old school pugilist. His looks were deceptive,

because he was devastatingly powerful and carried a pulverizing punch.

Cooney

entered the ring against Boone wearing emerald green trunks, which

boasted an Irish shamrock emblem. The buzz in the arena was electric and

in their corners both fighters pawed the matt like bulls readying to

charge, obviously affected by the enthusiasm of the crowd. The fight got

off to a miss-start when Boone and Cooney engaged before the opening

bell, and they had to be chased back into their neutral corners to start

the fight again properly. Cooney

entered the ring against Boone wearing emerald green trunks, which

boasted an Irish shamrock emblem. The buzz in the arena was electric and

in their corners both fighters pawed the matt like bulls readying to

charge, obviously affected by the enthusiasm of the crowd. The fight got

off to a miss-start when Boone and Cooney engaged before the opening

bell, and they had to be chased back into their neutral corners to start

the fight again properly.

As Gerry Cooney was rising up

through the amateur weight classes, he had been trained stylistically to

fight as a “boxer”. Styles mean everything in boxing, and fighters

develop their skills along certain well-defined lines of discipline,

based on what they bring to game. Some are “sluggers”, like Mike Tyson,

whose style was all about extreme aggression and knockout power. Many of

those types will work inside to the body, but there are perimeter

sluggers, as well, like a Tommy Hearns. Other fighters are “tacticians”,

like Evander Holyfield, who analyze their opponent’s skills and adjust

their game accordingly, fighting inside and out. The “boxer” is often

the showiest of the lot, which is what made Cooney’s choice to fight in

that style seem so odd. Muhammad Ali, Sugar Ray Leonard, and Floyd

Mayweather, Jr. were boxers. Those guys were extremely athletic, quick

and agile, none of which are traits one would ever associate with the

lumbering Gerry Cooney, and yet there he was, a graceless giant fighting

cautiously from the outside of the reach of his shorter opponents.

Cooney used his long left jab to steadily wear down the defenses of his

combatant, patiently waiting for an opening to step in and to the left,

and then to throw his trademark left hook.

Cooney was geared to deliver

his left as a hybrid punch, part upper cut, that could be aimed at the

jaw, but was often delivered with devastating effectiveness to his

opponent’s liver. It seemed as if he had been physically gifted for this

one punching motion, when his body mechanisms miraculously worked in

perfect unison to create a brief moment of ultra-violence. It was the

punch that you always knew was coming from Cooney, the inevitable

punctuation at the end of each brutally long sequence of jabbing

statements.

For most of the first four

rounds of the Leroy Boone fight, Cooney was satisfied to patiently

deconstruct Boone’s defenses, firing his heavy jab right through Boone’s

gloves, held high before his face. Boone was hoping to counterpunch,

because he saw what a lot of fight fans saw, which was that Cooney was

not a great defensive fighter. Cooney wasn’t that quick, and if you

could get inside his reach, you could find opportunities to land high

and low, and late in the fourth round Boone launched such an inside

attack.

Boone nailed Cooney with a

barrage of well-directed shots to the head but Cooney didn’t fold, and

so there answered was the big question that hangs over the heads of

every heavyweight fighter: can he take a big punch? Cooney had shown

that he could, at least one coming from Leroy Boone.

Cooney not only took the

punches, but he returned a barrage of his own, and when he returned to

his corner at the end of the round he seemed visibly to be enjoying

himself. It was as if Boone’s assault had snapped him out of a sleep

state and the brawler within him had been happily awakened.

However much Cooney may have

wanted to go into full attack mode, the Boone fight showed that he was

an uncommonly disciplined fighter. In the fifth round, Cooney resumed

the patient sparring style that had characterized most of the fight up

to that point, other than for the last minute of the previous round.

What did change was that Cooney started setting down on his left hook,

digging hard to Boone’s mid-section, and occasionally firing an

effective straight right. Almost exclusively a left-handed power

puncher, Cooney’s right was an arm punch that he could spot effectively,

but it lacked knockdown power.

In the sixth round, Cooney

resumed his patient demolition of Boone until a left hook to the liver

caused Boone to double in pain, and for the referee to call an immediate

halt to the fight. Cooney had destroyed a legit Black heavyweight, and

he was ready to move up in class.

* * * *

Jimmy

Young had been fighting professionally since 1969, and he was a talented

tactician who had lost a disputed title decision to Muhammad Ali in

1976. As a fighter, Young was called “the cutest guy in the business”

for his expert ring generalship. He surprised opponents, lulling them

into traps and striking with athletic precision. Young could only be

beaten by best-in-class fighters, and in a long career that included 19

losses his record reads like a history book of his era of boxing. All

the big names are there. Jimmy

Young had been fighting professionally since 1969, and he was a talented

tactician who had lost a disputed title decision to Muhammad Ali in

1976. As a fighter, Young was called “the cutest guy in the business”

for his expert ring generalship. He surprised opponents, lulling them

into traps and striking with athletic precision. Young could only be

beaten by best-in-class fighters, and in a long career that included 19

losses his record reads like a history book of his era of boxing. All

the big names are there.

By the time Young fought

Cooney in 1980, he was well-past his prime and he lacked the power to go

toe-to-toe with any of the heavyweights of the era. He was, however, a

highly-respected pro and another important step along the ladder in

Cooney’s ascendancy in the division.

Young came into the fight in

good condition, his career on the line. Cooney came into the fight with

a mustache, which made him look like a guy from the bare knuckle era of

boxing.

In the first round, Cooney

attempted to box with Young as he had with Leroy Boone, but Young was

too savvy. He parried Cooney’s jab and then worked inside, landing shots

before darting back out of danger, and robbing Cooney of the tactic

known to work against Young, which was to go to his body. Cooney

couldn’t get there, but rather was reduced to missing shots to Young’s elusive chin,

and that pattern continued through the second round.

At the end of round two,

Cooney’s corner men complained that Young had thumbed their fighter in

the eye, and Cooney came out for round three with aggression. Young

smothered Cooney’s attack, and Cooney went back to his pattern of

jabbing, while Young kept ducking inside and scoring.

Late in round three, Cooney

fired an upper cut that caught Young on the brow and opened up a cut

above his right eye, and Young seemed immediately to be in trouble.

While Young shook his head, trying to clear his vision from the blood

running down his face, Cooney pounced for the kill, firing a barrage of

combinations, some of which got through Young’s cocooning defense.

With a minute left in the

round, Jimmy Young started landing low blows, probably intended to stop

Cooney’s assault, though he did not get a warning from the referee.

Young backed Cooney into a corner and controlled him, lasting out the

round.

Cooney came out aggressively

in round four and while Young exchanged with him he became blinded by

the blood pouring into his eyes. Young’s corner called the fight at the

end of the round, and so Gerry Cooney had faced a difficult challenger

and prevailed on the strength of his lethal uppercut.

Cooney came away a richer and

wiser man. He had learned the value of the well-timed low blow, which

was a sneaky add to his fighter’s tool kit. Cooney’s uppercut left had a

way of landing south of the beltline without drawing the attention of

referees: a good trick to have in his bag in the event that an opponent

needed to be slowed.

* * * *

Ron Lyle was a Denver-based

fighter with a 39-6-1 record when he faced Cooney. A former gang member,

he had done seven-and-a-half years in the Colorado State Penitentiary

for second degree murder before starting an amateur boxing career,

eventually turning pro. Lyle was a big puncher who had scored victories

over big names including Jimmy Ellis and Ernie Shavers. And, if Gerry

Cooney’s marketability as a heavyweight contender was contingent upon

him beating a big-name Black fighter, Ron Lyle was at the very heart of

that darkness.

Lyle came into the fight at

6’3½” tall and 211 pounds. He turned out to be exactly the kind of

fighter whose style would be neutralized by Cooney’s outside game. Where

Jimmy Young had been able to game Cooney and get inside, Lyle looked

lost, floundering from afar and taking jabs, along with Cooney’s deft

left-upper cut and his occasional straight right to the body. In the

last minute of the first round, Cooney moved Lyle into the ropes and he

delivered a steady, patient barrage of right and left hooks to the body

and the head, and with only seconds left he delivered a left-hook to

Lyle’s liver that caused Lyle to collapse between the ropes, draping

onto the apron, finished.

* * * *

Gerry

Cooney often seemed like a one-handed fighter, like all he could do was

throw his left. His right was accurate, but of a lesser order in his

arsenal, and that was because he was a left-hander by nature. Somewhere

along the way, someone had trained him to fight orthodox, but his

dominant arm remained his left, so he had the perfect weapon to use

against a right-handed opponent. Gerry

Cooney often seemed like a one-handed fighter, like all he could do was

throw his left. His right was accurate, but of a lesser order in his

arsenal, and that was because he was a left-hander by nature. Somewhere

along the way, someone had trained him to fight orthodox, but his

dominant arm remained his left, so he had the perfect weapon to use

against a right-handed opponent.

Cooney’s demolition of Ron

Lyle had earned him the kind of respect that he needed to leverage his

celebrity and gain a shot at a heavyweight title. He had one person left

to get by to reach the #1 rank in the WBC and thereby get a mandatory

shot at the title held by Larry Holmes.

Ken Norton, who had been

fighting professionally since 1967, was the guy who Holmes beat to win

the WBC title that Cooney now wanted. Hollywood handsome, Norton became

nationally known by having beaten Muhammad Ali, breaking Ali’s jaw in

1973 before losing in two rematches. He was on the down side of his

career by the time he met Gerry Cooney in May, 1981. It would be

Norton’s last fight.

Cooney came out quickly and

tagged Norton with a straight right, following up with a barrage of left

hooks and rights until, 54 seconds into the first round, Norton was put

to sleep, slumping onto the bottom rope like a guy waiting for a bus.

* * * *

Gerry Cooney had earned his

shot at Larry Holme’s World Boxing Council Heavyweight Championship

belt, but the champ was going to make him wait for it.

Fighting

professionally since 1973, Larry Holmes had beaten every big name

fighter of his era. This included Ernie Shavers, Ken Norton, Mike

Weaver, Alfredo Evangelista, Ossie Ocasio, Lorenzo Zanon, Muhammad Ali,

Trevor Burbick, Leon Spinks, and Renaldo Snipes. Despite this

extraordinary record of accomplishment – he was 39-0 when he met Cooney

– Holmes was never accorded the level of respect that had been accorded

other great heavyweights, most notably Muhammad Ali. Fighting

professionally since 1973, Larry Holmes had beaten every big name

fighter of his era. This included Ernie Shavers, Ken Norton, Mike

Weaver, Alfredo Evangelista, Ossie Ocasio, Lorenzo Zanon, Muhammad Ali,

Trevor Burbick, Leon Spinks, and Renaldo Snipes. Despite this

extraordinary record of accomplishment – he was 39-0 when he met Cooney

– Holmes was never accorded the level of respect that had been accorded

other great heavyweights, most notably Muhammad Ali.

In truth, Holmes suffered by

being directly comparable to Ali, which made him seem more like an

imitator than a visionary boxer. Holmes had been Ali’s sparring partner

and had clearly gone to school on Ali’s moves. Ali had spotted Holmes

when the younger fighter was an amateur and Ali had brought Holmes to

Ali’s training site in Pennsylvania, where he paid him $500 a week to

work as his sparring and training partner. The two had similar size and

range, and they were of similar skill levels. Ali knocked out 61 percent

of his opponents, while Holmes knocked out 59 percent of his.

Where the mentor and protégé

differed was in the area of charisma. Even as he was defeating the

biggest names in the profession, Holmes demonstrated a dispassionate,

disengaged, workman-like attitude that seemed flat and boring, while

also more than a little condescending. He often seemed disrespectful of

his opponents, while he only occasionally flashed his own considerable

skills in any impressive display of boxing artistry. None of this

endeared him to the boxing world, and he was frustrated by their

displeasure, once verbally attacking one of boxing’s most cherished

personalities, proclaiming that Rocky Marciano couldn’t have carried his

jockstrap.

To

get to Larry Holmes, you had to go through Don King. To

get to Larry Holmes, you had to go through Don King.

Holmes was a principal asset

to Don King promotions, which presented Holmes’ fights in his

championship years. Holmes always said that he never made any money in

boxing until he became associated with Don King, but the flamboyant King

came with a lot of baggage. King had dropped out of Kent State

University to run a bookmaking operation. He had killed two people, one

ruled a justifiable homicide, while the second got him a second degree

murder conviction. He had stomped an employee to death over a dispute

involving $600. King was to spend four years in prison, but letters of

recommendation from Jesse Jackson, Coretta Scott King, George Voinovich,

Art Modell, Gabe Paul, and other high profile celebrities earned him an

early release. Resurfacing as a boxing promoter, he promoted the careers

of Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier, George Foreman, Larry Holmes, Mike Tyson,

Evander Holyfield, Julio César Chávez, Ricardo Mayorga, Andrew Golota,

Bernard Hopkins, Félix Trinidad, Roy Jones, Jr. and Marco Antonio

Barrera. Almost all of those fighters would eventually sue him for

defrauding them, but King settled most lawsuits with pay-offs and

avoided felony fraud convictions.

King’s ethics problem extended

to the narratives that he was willing to spin to promote his big money

bouts. He was a marketer, a brand builder, who gave the world "The

Rumble in the Jungle", the "Thrilla in Manila", and other recognizably

branded events.

King’s promotional strategy

for the Holmes-Cooney fight was a sign of the times, and an example of

gross irresponsibility in the pursuit of riches. King is still around

today, a Donald Trump endorser who thinks Bernie Sanders should be

Trump’s Vice President. Like Trump, King would throw gasoline on an out

of control fire if he thought it would get media coverage, and that is

exactly what he did in marketing the Holmes-Cooney championship fight.

King promoted the fight as a

racial spectacle, a disrespected Black champion going against a Great

White Hope. No White man had held the heavyweight title for 22 years at

that time, and King toured Holmes and Cooney around the country to

attend press conferences and promote the clash. The media darling Cooney

was on the cover of Time Magazine. Celebrities became obsessed with the

event, as did White supremacist groups who announced that they would

have snipers at the event to shoot Holmes as he entered the ring. That

prompted Black groups to announce that they would have armed members on

hand to defend Larry Holmes from attack.

By the time Holmes and Cooney

met, in the parking lot at Caesar's Palace, police snipers were

positioned on the roofs of all of the hotels surrounding the event site,

ready to respond if any of the proposed violence actually happened.

* * * * *

In a new age of hyper media,

and in a period when race relations were in a difficult new phase,

Holmes and Cooney became pawns in an evil enterprise; one that exploited

xenophobic fear using powerful new tools of audience manipulation. Larry

Holmes, in the Don King narrative, came to symbolize a Black community

that the White world would not recognize, and would not allow to achieve

its potential and its promise. Cooney, dubbed the Great White Hope,

became symbolic of dumb White America, and the segment of White society

most threatened by upwardly mobile Blacks. Cooney had been uncomfortable

with the fight promotion, saying that race had nothing to do with the

fight, that “we are all Americans” and so he won the broader PR battle

as the fight date approached, but there were complications. Tension

between the Cooney and Holmes camps grew more personal until finally

there was public acceptance of the notion that Cooney and Holmes hated

each other. That helped turn the event into a box office bonanza,

including a closed-circuit Pay Per View revenue stream for the live

fight, and rebroadcast rights sold to HBO, which ran the fight a week

later.

Eleven months passed between

the time that Cooney beat Ken Norton and the date when he finally got

his crack at Holmes. Part of the period of inactivity was intentional,

with Cooney avoiding tune-up fights for fear that a wildcard loss would

cost him his shot at Holmes’ title. Other delays were health related, as

at one point the fight was scheduled and then rescheduled for a later

date after Cooney hurt his shoulder in the gym. Some fight fans opined

that Cooney was scared, looking for an excuse not to fight Holmes, and

so the tension between the two fighters continued to grow. While Cooney

was sitting on pins and needles, biding his time, Holmes fought and beat

two more name opponents: Leon Spinks, who had beaten Muhammad Ali, and

Renaldo Snipes, who knocked Holmes down before finally losing to him.

That incident created doubt in some that Holmes, at 32, was still the

real deal, despite his unbeaten record. After Snipes, Holmes went into

the gym for six months of preparation before he finally met Gerry Cooney

for the WBC Heavyweight Championship.

* * * * *

On June 11, 1982, Gerry Cooney

entered the outdoor arena at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, where the

temperature at fight time hovered at more than 100 degrees, to the theme

from the fight film Rocky. He had grown in his public stature and

become the fan favorite, though he was the underdog in the fight. Fight

analyst Howard Cosell touted Gerry Cooney as being 6’7” and taller than

the aforementioned Primo Carnera, which was probably based more on

Cosell’s perception of the magnitude of the fight than on any late

growth in the still-young Cooney. Dressed in Irish green, Cooney entered

the arena, addressing fans along the way, cracking jokes and seeming to

be relaxed. Holmes entered to the Disco sounds of “Ain’t No Stopping Us

Now”, trotting down the aisle to the ring, apparently anxious to get on

with the contest that he had predicted he would win in 7 rounds, or

maybe in 4 if Cooney engaged him.

Diminutive Nevada District

Attorney Mills Lane, who had officiated many championship fights, was

the third man in the ring and he looked tiny standing between the two

big heavies. Announcing the fight for HBO, Howard Cosell wondered if

Lane would be physically large enough to control the two fighters.

Waiting in their corners for

the bell to sound, signaling the start of the first round, Holmes

bounced up and down like a giant spider monkey, while Cooney rocked back

and forth like a gorilla in a zoo cage.

ROUND

ONE: At the bell the two fighters approached and they

immediately fell into a pattern that would characterize much of the rest

of the fight, with Cooney coming forward, Holmes moving adroitly left

and right, firing jabs and moving; Cooney jabbing, hooking, sometimes

connecting.

For the first half of the

first round, Holmes looked too fast and accurate for the patiently

plodding Cooney, but then Cooney landed a left to Holmes body and the

fight started to change. Cooney threw a right to the body and then

landed a left below the belt. It appeared unintentional, but shortly

thereafter it happened again. Cooney threw hooks to Holmes’ ribs that

Holmes blocked with his arms, leading Howard Cosell to suggest that

Cooney’s power could make Holme’s limbs grow numb, as Rocky Marciano had

been known to do to opponents feeling his thunderous barrage.

Cosell’s invocation of

Marciano’s name played to the narrative for the event, that this was a

fight between an unpopular Black champion, who had insulted a beloved

White champion, and a Great White Hope who was calling him to account

for his actions.

It seemed apparent in the

first round that Holmes felt and was affected by Cooney’s power. He

switched his tactic, limiting his exchange to jabs and staying away from

Cooney, obviously uncomfortable with letting Cooney get to his body.

Just before the end of the round there was a flurry in which Holmes

landed a shot squarely on Cooney’s jaw, and it didn’t seem to hurt him

at all. Holmes must have returned to his corner wondering, if Cooney

survived that shot, how he was going to keep the Irishman at bay.

Between rounds, Cooney’s

mentor Victor Valle implored him to use the double jab, and he warned

Cooney against wild exchanges with the champ. “This guy isn’t shit!”

Valle told his fighter, but “be patient!”

ROUND TWO:

For most of Round 2, Holmes circled

Cooney, firing jabs, avoiding Cooney’s right leads, jabs, and left

hooks, but mostly avoiding the ropes. Cooney had a reputation for

destroying opponents that he could trap on the ropes, and Holmes kept

moving laterally to negate Cooney’s attack, stopping occasionally to

fire a sharp volley, before moving again. Then with a little more than a

minute left in the round, Holmes nailed Cooney with an overhead right

that sent Cooney lurching to the canvas. It looked like the doubts the

fight world had about the upstart Gerry Cooney – the Great White Dope –

were going to be well founded, but Cooney wasn’t done.

With 30 seconds left in the

round, Cooney stood up on rubbery legs, looking like a guy who might be

ready to go, but he suddenly recovered himself. Cooney seemed to clear

his head and as the round drew to an end he seemed to take control over

Holmes, firing jabs and lead rights and clearly winning the final

half-minute of the round.

My take, when the fighters

went to their corners, was that Holmes probably had a 10-9 and a 10-8

round on his ledger, a 2-0 lead in rounds, and was well on his way to

defending his title.

ROUND

THREE: At the start of Round 3, Holmes

squared up with Cooney and the two exchanged jabs until Cooney once

again landed a below the belt shot that made Holmes go back to his

circling strategy. Cooney scored again to the body, again landing a shot

that appeared low, and Holmes was clearly uncomfortable with those body

shots. He stayed at such a range that he couldn’t land his own long jab,

but Cooney pressed him and at one point he landed a series of left hooks

to Holmes’ head and the look on Holmes’ face turned to one of real

concern. Cooney began to stalk Holmes, landing another low blow that

seemed to warrant a warning from Mills Lane, but none came. Cooney

continued to score, following Holmes around the ring, and Holmes seemed

to be losing control of the fight. Bruising appeared around Holmes right

eye, where he had been absorbing Cooney’s hook. After getting nailed

with an uppercut left, Holmes began to fight back in an effort to regain

advantage, standing in front of Cooney and looking for another

opportunity to land his overhand right, which he did at one point but to

no great effect. Cooney won the third round, so by my estimation was

down 29-27, 2 rounds to 1.

ROUND FOUR:

Holmes came after Cooney to start the

fourth, standing flat-footed in front of him and looking to exchange

until Cooney again caught him with a shot to the body that made Holmes

decide to resume his jab-and-move game. Occasionally he would set for an

exchange but Cooney kept scoring, particularly with his much

under-appreciated right hand. Cooney was getting off first and it seemed

to throw Holmes out of his rhythm. For the last 30 seconds of round 4

Cooney landed to the body and head and when Holmes went back to his

corner he looked deflated. On my card, Cooney had pulled even in rounds,

and was down only 38-37 in points under the 10-point must system.

ROUND FIVE:

Cooney was clearly gaining in

confidence, and he practically leaped out of his corner at the start of

Round 5, going after Holmes with his stiff jab. Fight commentator and

former Welterweight Champ Sugar Ray Leonard surmised that the age

difference was beginning to show, as the 25-year old Gerry Cooney seemed

energized while the 32-year old Larry Holmes was looking a little tired

and a lot like a guy who didn’t want to get hit anymore.

For the first two minutes of

Round 5, Cooney stalked Holmes, nailing him with jabs and body shots as

Holmes retreated away, firing almost no punches at all, obviously

reluctant to do anything other than defend against Cooney’s measured

onslaught. Inside the one-minute mark, Holmes scored with a couple

overhand rights, one as solid as that which had floored Cooney in the

second round, and then with fifteen seconds remaining Holmes threw a

nifty left-right and spin-away combination that seemed to remind him

that he had skills. After getting beaten for most of the round, Holmes

finished the 5th bouncing on his toes and looking like a re-energized

guy. On my score card, the fight was 47-47, with Cooney winning 3 rounds

to Holmes’ 2.

ROUND SIX:

Round 6 felt much different from how

rounds 3 through 5 -- the Cooney rounds -- had felt. Holmes had clearly

experienced some shot of energy and confidence, and he came out in Round

6 looking in charge. As discoloration grew around Cooney’s left eye,

Holmes exhibited athletic quickness, using his deft jab, and moving,

neutralizing Cooney’s attack. But then, about a minute into the 6th,

Cooney nailed Holmes with a right that made Holmes’ legs go rubbery for

an instant, and then Cooney moved into stalking mode again while Holmes

went into retreat. He landed a right into Holme’s ribs that sounded like

a bass drum and you could see energy drain from Holmes’ aging body.

Cooney won exchanges with

Holmes, but with 30 seconds left in the round Holmes landed another

overhead right that made Cooney’s legs go rubbery. He staggered around

the ring as Holmes continued to pummel him, almost going through the

ropes at one point before he was able to grab hold of Holmes to stop him

from throwing punches. When they broke, Holmes went for the kill but as

the bell rang at the end of the round Cooney landed a left that sent him

back to his corner thinking he could still win.

Round 6 might have been scored

a draw, which would have made it 57-57 as the two fighters went to their

corners to prepare for the 7th round of a scheduled 15 round

fight.

ROUND

SEVEN: Cooney came out for Round 7 with

Vasoline covering a cut by his left eye and he was ready to exchange. He

threw a beautiful straight right that just missed, but then hit Holmes

with another low left hook that finally got him a warning from Mills

Lane. It had the effect it had all fight, as Holmes retreated and moved

rather than standing in one place to take more punishment. The two

exchanged at the center of the ring before Cooney landed another left

hook to Holmes’ body that again echoed like a bass drum. He followed

with two more and Holmes retreated, staying at a distance, often

carrying his hands low until Cooney pulled back within range. Cooney

nailed Holmes with another hook to the body, but instead of wilting

Holmes suddenly started bouncing on his toes, again showing an

inexplicable ability to re-energize, at least in spurts.

Cooney kept coming, despite

Holmes show of confidence, and he scored with both hands while Holmes

missed with a winging right before getting caught with another low blow

that brought another warning from Mills Lane. In truth, Cooney should

have been penalized by this point, because he had been landing low blows

all night, and it had been having a significant influence on the fight

with Holmes retreating to recover after each blow, becoming ineffective

as an offensive force in the process.

I believe the 7th

round could have been scored even: 67-67, with Cooney still ahead 3

rounds to 2.

In Cooney’s corner, Valle

implored Cooney to get inside of Holmes’ jab, to crouch and go in low,

which was not really his fighter’s forte. Cooney’s cut near his left eye

was not looking good, and Valle feared the doctor would stop the fight

before Cooney could stop Holmes.

ROUND

EIGHT: In the 8th, Cooney

kept coming forward, trying to move in on Holmes, who continued to

circle outside, sometimes stopping but losing brief exchanges before

going back on his bicycle. Cooney landed body shots, and right leads to

the head, but Holmes didn’t seem hurt by them as he had in the earlier

rounds. It seemed as if the steam was going out of Cooney’s punches, but

he kept coming forward in a patient, deliberate way, and firing big

shots.

In the last 20 seconds of the

round, both fighters landed but neither seemed affected by the other’s

power.

Round 8 had Cooney landing

more shots. He may have moved ahead 4 rounds to 2, and 77-76. On the

other hand, Holmes was giving the impression that he was fresher and

under control, so who knows, the judges may have seen it differently. As

it turned out, it wouldn’t matter.

ROUND NINE:

In the opening moments of the 9th

round, Cooney nailed Holmes with shots to the head, but Holmes didn’t

seem to be hurt by them, and then Cooney’s cut opened and blood started

pouring down the left side of his face. Cooney attacked with a

combination, perhaps sensing that his ability to remain vital was

draining away.

At the 1:30 mark in the round

it began to appear that Cooney couldn’t see out of his left eye, and

Holmes hit him with a lead right. Cooney kept coming, but most of his

shots were being blocked by Holmes’ arms, held high between them. Cooney

landed a left hook to Holmes’ jaw that in the early rounds might have

removed his head, but at 1:20 in the round he was no longer feeling that

Cooney had any power remaining.

With about a minute left,

Larry Holmes landed a straight right, which for some reason caused Mills

Lane to rush between them to look at Cooney, perhaps expecting to see a

need to stop the fight and have the cut looked at. Inexplicably, he

darted away as quickly as he had come between them, and the fight

continued.

With less than 30 seconds left

in the round, Cooney hit Holmes with a left hook way south of the belt

line and Holmes doubled over in pain. Mills Lane jumped back in to pause

the fight to give Holmes time to recover, and to send the fighters to

their corners.

While Holmes was in his corner

recovering from the foul, his trainers gave him water and doused him to

refresh him, while all the while Cooney stood on the other side of the

ring getting no aid at all, and looking like a guy who had been in a car

accident. His face was bruised into a darkening blue mask of damaged

flesh, but he stared hard at Holmes like a guy who was on a mission and

who was prepared to go out on his shield.

Holmes seemed fine when the

fight resumed, and Cooney came right after him, throwing power hooks and

a right, not with the zip he had earlier, but still threatening.

Cooney probably won the round,

but a point penalty for the low blow made it even. On my card, Cooney

was leading 86-85, with Cooney up 5 rounds to 2.

In the corner, Cooney

expressed concern about his cut, to which his trainer said “Don’t worry

about it.” In Holmes corner they pleaded “Don’t let this guy take it

away from you!”

ROUND TEN:

At the start of the 10th,

both fighters exchanged, with Holmes landing a good straight right and

Cooney taunting him before returning a volley of punches. The two

exchanged until Cooney got the better of it, landing two more low blows

in the process, and Holmes retreated and then put Cooney in a bear hug.

Cooney landed a straight right

but though it was on the chin, Holmes didn’t move. They exchanged jabs,

and then Cooney landed another combination that included low blows to

the body. Cooney seemed to get stronger and he hit Holmes with some

shots that jarred him. In fact, in Round 10 Cooney was landing punches

at something like a 4-to-1 ratio to those landed by Larry Holmes. At one

point, Cooney landed eight consecutive shots before Holmes suddenly

nailed him with a lead right. The two exchanged big blows, with Holmes

landing four giant right hooks to the head in the final 20 seconds, but

Cooney kept throwing and landing.

When the bell sounded for the

end of the round, the two fighters brushed against one another and

touched gloves in a way that said these two now had each other’s

respect, however much bile may have been spewed in the buildup to the

event. Gerry Cooney had proven to the world that he was no bum. And

Larry Holmes had shown what had always been undeniable about him, which

was that under that dispassionate demeanor beat the heart of a lion, the

will of a champion.

The round may have been even,

which would have made the score 96-95 Cooney, with Cooney still up 5

rounds to 2.

ROUND

ELEVEN: Cooney’s corner did a tremendous

job on the eye, and he came out for Round 11 looking better than he had

in a few rounds. The two came together and exchanged punches. Cooney hit

Holmes with another low blow and Mills Lane immediately deducted another

point from Cooney’s score.

Holmes seemed to rest for the

first two minutes of the round, with Cooney firing and scoring while

Holmes was satisfied to play defense, marshall his energy, and watch for

an opening for the lead right, which had been his best punch all night.

Cooney continued to fire and score, landing a couple more low shots that

got him another lecture from Mills Lane. Then, with 30 seconds left in

the round, Holmes went on the attack with an eye on stealing the round,

but he wasn’t effective. Cooney was fighting better defensively than

anybody thought he could, slipping Holmes’ big punches.

If the round went to Cooney,

he was up 106-104 and 6 rounds to 2.

I noticed a minor change in

Cooney in Round 11. Tired, he began to have moments where he would come

out of his fighter’s stance, moving his right foot forward so that he

was squared up with Holmes, which put him in a bad defensive position.

Sometimes tired bodies don’t behave the way you would want, and Cooney’s

was starting to have a mind of its own.

ROUND

TWELVE: When Round 12 began, Cooney was

still slipping into that stiff-legged, upright posture, not really a

fighting stance but rather a pose his body chose for him out of physical

exhaustion. Cooney began punching in slow motion, and Holmes saw that

and he sharpened his jabs. Cooney kept coming, occasionally surprising

Holmes with a rapid combination driven by energy that seemed impossible

for Cooney to summon, and yet there it was.

In the last 15 seconds of the

round, Holmes reopened Cooney’s cut, hitting him with six hard lead

rights.

Holmes probably won the round,

pulling within one to 115-114, trailing 6 rounds to 3, with 3 even.

In Cooney’s corner, Victor

Valle pleaded with Cooney “to get rough with this guy”, as if the

previous 36 minutes of low blows and shots to Holmes’ head had been mere

introduction. In Holmes corner he was told, frankly, “We need these

rounds!”

As Cooney rose from his stool,

Victor Valle chided, “You waited too long for this guy!” It was as if he

knew the moment had passed.

ROUND

THIRTEEN: It was still 89 degrees when

the fighters got slowly up from their stools to start the 13th round.

They resumed the same steady, patient exchange of firepower that they

had exhibited the whole fight, with Holmes landing a shot and Cooney

coming right back with more.

Cooney’s face looked a mess

again, his cut torn back open by Holmes’ jab. The two fighters kept

exchanging big shots and then suddenly, visibly, all of Cooney’s

remaining power drained from his body and he appeared to be staggering,

out on his feet.

Holmes saw it and attacked,

landing combinations for the first time all night. Cooney lost his

balance and fell back into the ropes.

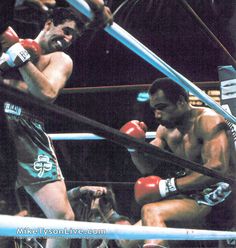

Mills Lane stepped in,

apparently to start a knockdown count though Cooney had never gone to

the matt, but before he could start it Cooney’s trainer Victor Valle

leaped into the ring with a white towel and stopped the fight himself,

saving his Gerry Boy further damage.

Larry Holmes had successfully

defended his WBC Heavyweight Championship.

Celebrating in Holmes corner

were Don King and Jesse Jackson.

POST-FIGHT: “I’m still the baddest heavyweight in the world

and it’s time for you to give me some credit,” Holmes said to the fight

analyst Larry Merchant in a post-fight interview. Holmes spoke

respectfully of Cooney’s all-around fighting skills, suggesting only

that he needed to improve his chin. The fight, after all, had come down

to one thing: Larry Holmes’ ability to survive the shots of a super

heavyweight. Holmes spoke articulately about having followed through on

his plan to counter Cooney’s punches. “I think I mastered everything

that Gerry Cooney had,” he told Merchant. “I am a great boxer, Larry,

and the world know (sic) it.”

Cooney was humble after the

fight, respectful. “Larry Holmes is the champion of the world,” he

acknowledged. Cooney said that going into the 13th round told

him that he could be a 15-round fighter, meaning someone who could fight

for championships, but something about Cooney’s quiet and sensitive

little boy voice seemed to say that he was done, that this fight with

Holmes had been it for him. It would be 27 months before he would fight

again, beating the undefeated Phillip Brown by TKO. Two months later, he

beat another good fighter, George Chaplin, also by TKO. Cooney then

disappeared for another year-and-a-half before knocking out another good

fighter, Eddie Gregg. A year later he lost to the undefeated Michael

Spinks, before fighting one last time, 30 months later, against the

resurgent George Foreman. He lost those fights by technical knockout and

then retired.

Whatever pressures Holmes and

Cooney must have felt, and however much they had been encouraged by

their promoters to disparage one another, both came away from their

fight with a genuine mutual respect. Both fighters confronted their

doubters and performed at levels beyond what anyone could have

reasonably expected. Heavyweights don’t usually throw and land the

number of punches that Holmes and Cooney had. There in the parking lot

of Caesar’s Palace they put on a show for the ages.

As a media event,

Holmes-Cooney mercifully ended with all the flash of a Sunday dinner

with grandma, with everyone being civil and polite. As a fight, it

earned its spot right up there with the most memorable in the history of

the heavyweight division.

|